.

|

.Section Four - about the life and times of the family of William Squires and Mary Ann Harrowell.

|

This section is intended to add colour to the facts reported in Sections One through Three. Wherever I had a question about the logistics, comprehension or relevance, I did some research and have added these findings.

At the conclusion of this section, Alice's story picks up again on the page for Archibald Thomas Longhurst, the Canadian whom Alice (Lulu) married in 1923, in Barrie, Ontario.

Briefly, about life in London, England, around 1903...

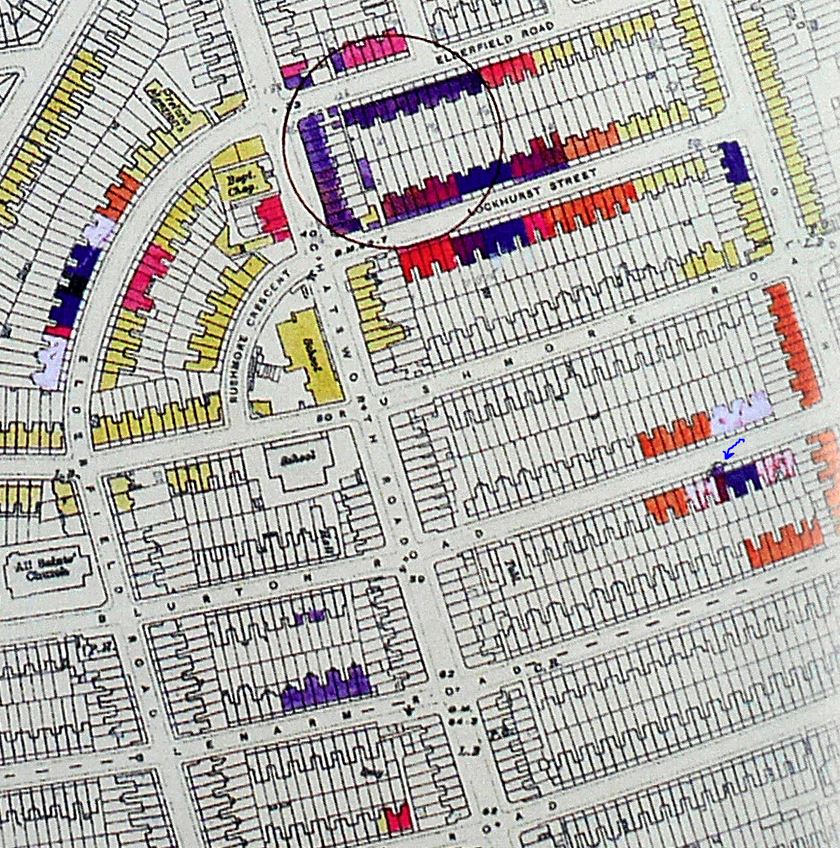

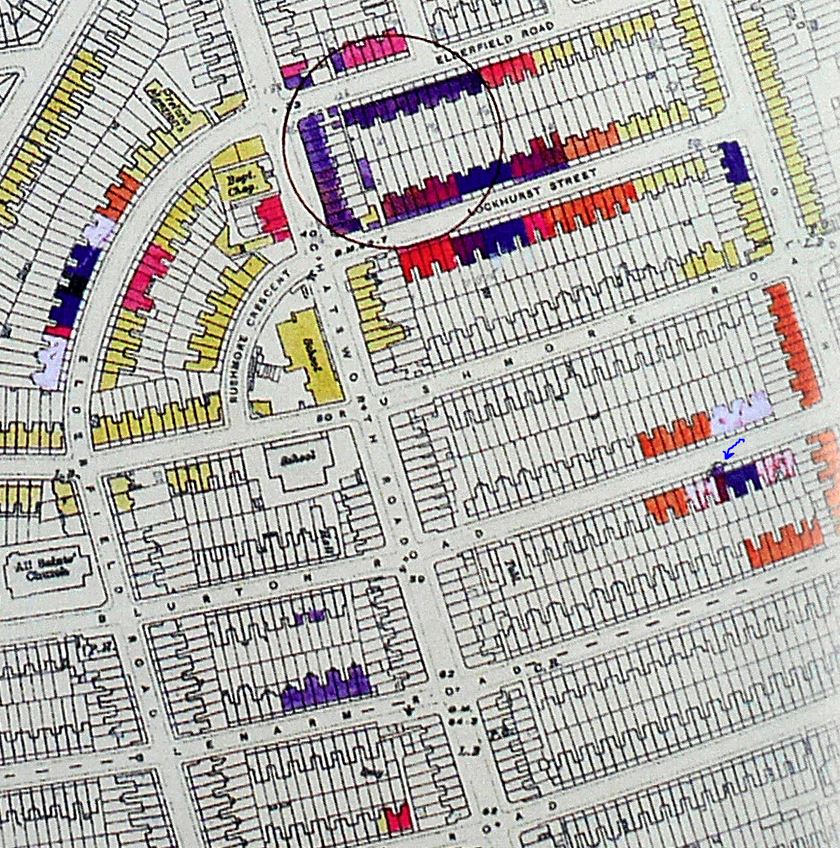

The immediate family of Alice Squires lived in a borough in East London known as Hackney. Within Hackney, the district they lived in was known as Lower Clapton. Chatsworth Road, a major road running north and south, seems to have been the "main street" for the Squires family. This map, made by Kelly's Directories, shows Chatsworth Road as it was in 1894. Notable on this map are Chatsworth Road, Blurton Road (which intersects with Chatsworth) and Maclaren Street (which runs between Rushmore and Redwald).

|

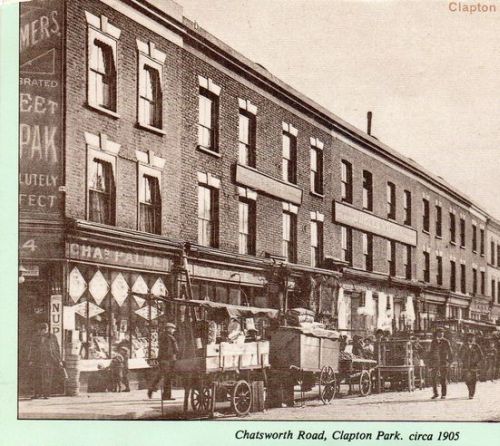

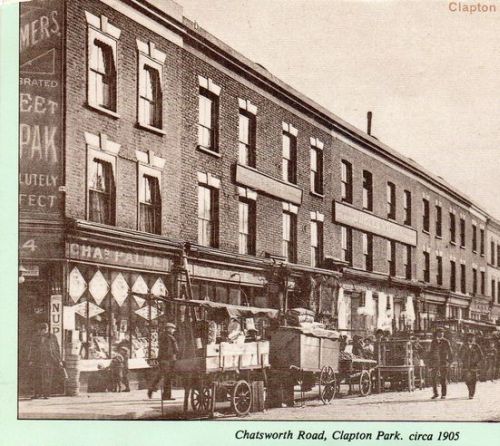

Since the time this area was built (circa 1865), storefronts have lined both sides of Chatsworth, occupying the lower level of three-storey architecture. Store owners may well have lived above, and perhaps in or behind, with the remaining space being rented out by the property owners.

According to notes made for Charles Booth's survey (more about this below), Chatsworth was "one of the chief shopping streets of the district". "On Saturdays there are stalls on both sides of the road. This day gooseberries were selling in the greengrocers' shops at 2d and 1d per lb. Greengages (a kind of plum) fair at 4d, red currants 3d. Lettuces at 1d and 2d each, according to size. There were some good stationers shops selling newspapers and good bakers at the corners."

To give some perspective, this picture (above) is actually two period photos merged together to make it appear as if one is looking north, in the direction of 84 Chatsworth (relevant below), from the corner of Chatsworth and Clifden Road. The pictures can be seen in their original versions at yeahhackney.com, as originally shared by postman Ken Jacobs who worked in this area, and who is recognized in a book about working class jobs in Hackney entitled Working Lives (in two volumes). On the right, the first break in the buildings is where the intersection with Dunlace Road would be (a key bit of information in that the SE corner would be #34 Chatsworth; click to jump ahead). If each store is two second-storey windows wide, then there appears to be eleven stores in this block. The next block break, for Glenarm Road, is also visible. One more break and you would be at Blurton Road. Chatsworth appears to be quite wide rendered this way. Today, from sidewalk to sidewalk, there is room for parked cars on both sides and two-directional traffic.

In 1899, people living along Chatsworth were, on average, in "the pink" according to the colour coding on the poverty map (

below) - that is to say, they were "fairly comfortable, with good ordinary earnings".

From Wikipedia... "Like many other parts of East London, Lower Clapton is socially diverse and multicultural. Chatsworth Road, which had a regular market until the 1990s, still provides many amenities for people who live in the area. A new Sunday market has been established here since December 2010. The shops and restaurants on Chatsworth Road reflect the diversity of the surrounding streets, offering (international) produce alongside butchers, bakers and greengrocers."

|

(Click on this image to run the video in your media player, or right-click and "Save As" to download the MP4 to your computer.)

|

This BFI (British Film Institute) movie of a wide London throughfare in 1903 appears busier than life on Chatsworth probably ever was, but it does give some sense of the times. Horse-drawn buggies and buses, awnings and barrows, vested suits and street-sweeping dresses and skirts. Hats everywhere. Advertising for Lipton's, Bovril and Nestlé, Pears, Reckitt's Blue and Kodak - all that's missing are the sounds and the smells. People are outside, the streets were a place to be alive. Residences would not have the amenities they have today. The streets (or the pubs) would have been where your friends could likely be found (no email, texts or telephones to track them down). The streets would have been where the news came from - a newsboy selling the Hackney Gazette - rather than a newsreel, radio, TV or the Internet. The streets would have been where you shopped, no trekking off to the big box stores or indoor malls. For common kids, the streets would have been where you played - no drive to the local arena or soccer field or pool, no martial arts classes or dance studios. Your food, your clothes, and other items came from the stores along the streets or from the street vendors out front of them. Your local apothecary offered the earliest medicines, medieval concoctions and quackery to try and keep you out of the infirmary - if you could afford such.

The occupation of carman, around 1903...

William Squires was employed as a carman, (in this case, meaning a deliveryman using a horse-drawn cart) for Messrs Palmer & Co., grocers of 84 Chatsworth Road, Hackney. I can see carman being an abbreviation for carriage man or cart man, or a combination of both. (If one says carr-y-man fast enough, like an Englishman might, the "y" almost naturally drops out.)

From Barnardo's documentation... Mr. Squires - "of exemplary character" and "well-liked" - was a carman for Messrs Palmer & Co., grocers of 84 Chatsworth Road, Hackney.

By 1903, William had had this job for more than eleven years, from about the time he was twenty-three years old. This was also from about two years before he was married. Having a steady full-time job would have been an unwritten requisite for marriage. William's wages in 1903 were known to be 25 shillings per week.

In the simplest terms, being a carman meant working long hours and being outside and unsheltered a good deal of the time. This picture is of an open-air grocery delivery carriage, with young carmen, from British Driving Society's Pictorial History of Trade Vehicles.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Title page

|

323

|

324

|

325

|

326

|

327

|

328

|

329

|

330

|

331

|

332

|

333

|

The job and life of a carman are well described on these pages of Charles Booth's Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London. Other volumes in Charles Booth's series describing other occupations and living conditions can be found at this link.

I can see two possible perks for William, with delivering for a grocery store. The first would be the store iself with the availability and proximity of the wares. When something was needed, William would likely be able to pick from the best of any item that suited his needs and could be afforded - first to pick from the heads of lettuce, for example, with the ability to pick from what's on the counter and what's not. If the store was to have something on special, it was unlikely that those working there would miss out. Soon-to-be-spoiled foods would have been available to him also, at an appreciable discount. This is a great advantage over someone coming to the market just once a week. An aside to this is that William would not have to make a special trip to the grocers (avoiding the expense of resources or time), he was probably there as many as six days a week as it was (although Sundays, for all, and Mondays, for those in his occupation, may have been days off). And being able to bring food home six days a week should have meant that the family's food at home had less of an opportunity to spoil.

Being a deliveryman, the second perk may well have been that of earning service tips. From Charles Booth's Inquiry, page 328 in the volume above, this comment about tips... "At one time tips were almost a system, but are no longer usual, excepting perhaps with the men engaged in parcels delivery, who may still substantially augment their wages this way."

Although it is unlikely that a poor East London family would opt for delivery if they could in any way get to the store and back, for deliveries to the better-off clients of Palmer's grocery store there may well have been tips. A reasonable amount of these tips could have wound up in William's pocket at the end of the day, especially if he was "well liked", as reported.

To estimate what the tips might bring in, consider that a pizza delivery person, for less effort, gets a tip of about $2 today. "Eight eggs for sixpence" in 1901, eight eggs for about $2 today. An efficient grocery store's deliveryman might be able to make 30 deliveries in a ten-hour day. Even if just half of these deliveries gave the deliveryman a tip of 6d., that's 90d. a day, perhaps 2s. a week.

The 25s. wages William was being paid is about 10% below the union rate of pay for carmen operating one-horse vans. For an employee with eleven years service at the same company, this seems to reinforce the likelihood that there were tips and that there were these other perks.

In William's case, nothing is mentioned about who owned the horse and carriage, or who was paying for the feed and upkeep, but with no mention of the horse and carriage as being left to the family or being sold by the family, I would take from this that they were not his and he was not paying for feed or upkeep. I would think it possible that a grocery store might own their own vehicle so they could advertise on it (see period photo above), or advertising in general on a vehicle might help defer the costs of operation for whomever the owner was (see period video above).

The rigours of being a carman (at times, leading to chronic issues with rheumatism and bronchitis) may well have led to William dying of pneumonia, in the winter of 1903.

The occupation of charwoman, around 1903...

Char is an olde English way of saying chore. A chore is a bit of work, often tedious and menial, but necessary nonetheless. A charwoman would equate to being a chore woman, a woman who does chores for a paid wage - cleaning, washing, laundry and the like, for pay. Charwomen could be employed by businesses or households. The work could be full time, but was often part time, or was a combination of several different part time situations that added up to being full time in the number of hours. The position would not be "live-in" (that would be a maid or housekeeper). A cleaning woman's job today would fit this description. One of Carol Burnett's characters was the Charwoman, you may remember.

By the late 19th century, char woman would more often mean domestic, rather than commercial, or office, cleaner, but was still used by hotels and the like when advertising. (Click on image below to see want ads.)

In 1903, 33-year-old Mary Ann Squires had five children and one on the way when her husband died. Mary Ann had been supplementing the family's income by working as a charwoman for a Mrs. Bainton of 57 Powerscroft Road up until that time. After William's death, Mary Ann continued to do so until the imminent birth of daughter Amy Ella (in August).

The Bainton family, living at this address on Powercroft (middle house in photo), was "fairly comfortable" according to the poverty map (learn more below). While there were want ads for every kind of job, including charwoman (like the one above found in a searchable period Welch newspaper online), it would not surprise me to learn that William had learned of the job opening at the Bainton's home while delivering groceries there.

To get to the Bainton's house, Mary Ann probably walked along Blurton until it more or less ran into Powerscroft. Another half a dozen houses and she would have completed the three-tenths of a mile walk in under ten minutes. This route takes Mary Ann across Chatsworth not far from where her husband was employed, so I expect that there was many a day she stopped in at the store on the chance he was not out on delivery, and perhaps on the return to do some family shopping. If the employment with the Bainton's had been going on over the several years the family lived on Blurton, there would have been many a day Mary Ann would have made the walk and worked while at some phase of pregnancy, and certainly this was the case while carrying Amy.

Of note... The Reverend Watson lived at 54 Powerscroft Road, across the street from the Bainton family. It is highly likely that he had known, or known of, Mary Ann and family for a period of time, having bumped into her occasionally on the street or having heard about her from Mrs. Bainton, or the obvious - having the Squires family in his congregation. And perhaps William had delivered groceries to his residence also, or the Reverend had met William while he was making his rounds. No surprise that it was the Reverend that tried to help with the fostering out the two eldest children and it may well have been he that made social services aware of the family's difficulties in the first place.

Since there were many children at home, and since William's work day was long, they must have had a babysitting arrangement with the neighbours for the children not in school yet. This makes it harder to get the full benefit of the wages earned since some of it may have been going to a sitter.

One would think that finding out what charwomen earned would be a simple task, that this information would just jump out of an Internet search. Well, it doesn't. I did find that, for laundry work, (four or five days a week, from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m., with three-quarters of an hour for dinner and half an hour for tea), washers made 2s. 6d. to 2s. 8d. per day. If this in any way equates, then a charwoman working perhaps four hours on a given day might expect to pocket about four/tenths of this 47d., or about just under one shilling per shift. Working part-time, five days a week, four hours a day, could therefore net about 5s. for a housewife like Mary Ann. Working 50 weeks a year like this, Mary Ann could add £12 10s. to the annual household income.

Wages, and the cost of living, in 1903...

At this point, it seems helpful to look at the money situation. As I have learned, prior to 1971 when the U.K. went "decimal", monetary amounts were expressed as pounds (£), shillings (s.) and pence (d.), where £1 = 20s. = 240d. This system is abbreviated as Lsd. Noting an amount as 1/10/6 is a way of saying 1 pound, 10 shillings, 6 pence. If guineas are mentioned, one of them was worth 21 shillings, pre-decimal.

William's carman's wages were noted in Bernardos documentation as having been 25/- per week which follows to mean 25 shillings and no pence. Tips might bring another 2s. per week. Working as a grocer's deliveryman would have been beneficial in a variety of ways, with some of them monetary. Mary Ann's earnings as a part-time charwoman is estimated (above, in the information about charwomen) to be £12 10s. This would put the family's income at £82 10s. annually.

The common wages earned and the typical expenses of people living in Victorian days has been assembled on Lee Jackson's victorianlondon.org site, specifically this webpage. Be sure to click where directed to reveal the volume of information at that site. Under the banner of Family Budgets, there is one specific section that seems quite relevant to this young family... From the Cornhill Magazine, 1901. FAMILY BUDGETS. I. A WORKMAN'S BUDGET. by Arthur Morrison. I have snipped a few things from the magazine to show here on a local page. This is a must-read for any real understanding of this family's story.

The Victorian age ended in 1901, with the beginning of the Edwardian age, but this should not make the comparison made any less informative for the sake of two years.

William Squires' employer's address in 1903 -- Messrs. Palmer and Co., grocers, 84 Chatsworth Road, Hackney, London, UK.

Note : this address is per the Barnardo's documents, one mention there, taken on their good authority. The period Directory, though (which itself can be wrong), shows a different occupant at 84 Chatsworth from at least 1901 to 1905.

First, about 84 Chatsworth. If not the correct address, it is the right neighbourhood. 84 Chatsworth is located about halfway between Blurton Road and Rushmore Road, on the east side. The Squires family lived at 120 Blurton which is just around the corner from #84, no need to even cross the road.

This Google Streetview shows 84 Chatsworth as it was in 2012, when the storefront was being renovated, the structural elements and brickwork unlikely changed much since 1903. Whether or not Palmer's grocery store was ever there may be partially determined by the coming of Arthur Toms, established in 1906. A retailer of local fare, a seller of meat pies and live eels, period directories show a series of annual entries for Toms at #84. The century-old Arthur Toms sign, revealed during the renovations at modern-day #84, has the number 84 on it, twice. Partially determined in that no renumbering occurred, as can happen.

Charles Palmer, grocer...

Was a grocer named Palmer ever the occupant of 84 Chatsworth? In the 1874 Hackney Trade Directory, there is a record for "Palmer Charles, grocer, 145 Well Street", likely the same person behind Messrs. Palmer and Co.. 145 Well Street is only about 1.1 miles away to the southwest of 84 Chatsworth, a 24-minute walk. Homerton is on the way.

In the 1901 Kelly's London Suburban Directory. [Vol. I: Northern. Part 1: Street & Commercial Directories], page 61 of the book, image 115, for Chatsworth Road, "Palmer, Chas., grocer" is shown at two locations on Chatsworth, 34 and 116. There are entries for all of the other Chatsworth addresses also, numbers 1 through 137 and 2 through 182, view locally Chatsworth addresses as a pdf. These addresses on Chatsworth Road would be businesses, professionals, self-employed individuals and the like that William and Mary Ann may have had dealings with in their day-to-day lives. 1901 is about as close as this source of commercial directories has to the year William Squires died and Alice and Amy were given up to Barnardo's Home. To see the available directories usable in this section, visit University of Leicester, Special Collections Online. Choose London.

The two Chatsworth addresses were not the only locations Charles Palmer had grocery stores at in 1901. "Palmer Charles, grocer, 34 & 116 Chatsworth Road, Lower Clapton NR; 47 & 64 High Street, Homerton NE; 133 High Street, Walthamstow & 123 Stoke Newington Rd N". Directory entries look like this, when by last name...

And this was not the only directory, type or year, that Charles Palmer, grocer, turns up in. Suffice to say that William Squires had latched onto a decent job with possible future advancement.

View the full page online 1901 Directory link, but to page 753, image 806 of 928, or locally Palmer as a surname in the commercial directory. View Palmer, Charles, grocer in the entries for High Street in Homerton. All of these addresses are within a just couple miles radius of their center.

When browsing through period pictures of London online I came across a large block of them at Pinterest shared under the name Alan Russell, with this descriptor "Hackney & London Local history research". I take it Alan has assembled these images as part of his research into Hackney and London (which is what this webpage is, although not specific to either Hackney or London, but to a family ancestor instead). One of the photos jumped out. It shows the name CHAS (Charles) PALMER above a store's windowed front. What looks to be the original postcard caption in the upper right reads: "Clapton Park, - Chatsworth Road". A title across the bottom, outside of the image, reads: "Chatsworth Road, Clapton Park, circa 1905". The title looks added-on, like the postcard had appeared in a book. The image is slightly crooked as a scan from a book might be if unedited.

The picture has been taken looking southeast. 8' shadows of two men walking on the road at a casual pace, shadows that point in a northeasterly direction, puts the time of day to be late afternoon. The store awnings are not out suggesting a somewhat overcast day. A child looking in a window is having to shade his eyes from the reflected light. Goods on carts out front are not covered. The road looks dry, no evidence of rain or snow. Hands in pockets, though, suggests early May or early October.

Knowing the street numbers on Chatsworth that Charles Palmer did occupy, this is clearly 34, and not 116, based on the visible number above the entrance being "4". This tells me that the picture has been cropped in an unfavourable place, especially since the signage above the door has also been cropped. If centered, as the surname would be, the cut off words would be ____ MERS, ____ BRATED, ____ EET, ____ PAK, ____ LUTELY, and ____ FECT - all this above _ 4. The top of the facade is also cut off. A triangle appears below PALMERS giving it about a 30º slope up while making PALMERS look like the font is italics. A bit of a second triangle appears above PALMERS in balance, giving the whole the appearance of a logo. I could fill in some of the blanks this way: PAL(MERS), CELE(BRATED), SW(EET), ____ PAK, ABSO(LUTELY), PER(FECT), above 3(4).

This all appears to be printed on a hanging banner in front of the brickwork above the entranceway since there is no brick pattern behind the lettering. The 34, though, would be semi-permanent, light lettering, perhaps gold in colour, on dark wood. It can be assumed that CHAS appears somewhere above PALMERS and that there must be an apostrophe following PALMER before the S. This makes CELEBRATED the modifier of PALMER, the man or the store, not the SWEET product he is advertising. Taken as a whole, the banner can now be assumed to read: "CHAS PALMER'S CELEBRATED SWEET ___ PAK ABSOLUTELY PERFECT", words one above another.

In searching for SWEET ___ PAK, nothing has been found, but the implication is that this is some kind of food, sweet-tasting; bakery products or confections perhaps. There is a lower sign beside the door that reads, in vertical letters, NUP, with room for another two letters or so beneath. The NU is separated from the P by a horizontal line. Putting this together with the ____ P + two letters AK on the banner, I now make that word or phrase out to be NU PAK. A sweet treat in new packaging? Could be. A search for SWEET NU PAK or NUPAK for that time yields nothing, though.

The store appears to be no more than 16 feet across. I can confirm that Palmer only occupies the space of one storefront because the neighbouring store does not have the same diamond-shaped window signage and, moreover, the store owner's name can be gleaned from the 1901 Directory - T.C. Corfe, furniture dealer, occupying numbers 30 and 32 Chatsworth at that time.

The entranceway of #34 is on an angle (which can only be 45º given that the entranceway is appears to be centered) leading to the Dunlace side. Google Streetview. There appear to be two flats above the store, then and now, that seem accessible from the rear. The Dunlace side shows a depth of about 32', if all store and storage, with glass windows going only about 10' beyond the door face, perhaps as it was in 1905. The entryway itself looks to be 6' wide making the banner above it, in Charles Palmer's time, out to be 6' wide also. An archway of original brickwork beside the front door on the Dunlace side, that can be seen in Streetview but cannot be seen in the period photo, suggests access to a basement.

In searching for another instance of someone advertising a product of the same name, where I could see NU PAK as a whole, nothing came up. This seems to be an exclusive to Palmer's stores. It is not known if all of his stores advertised the same product at the same time. In furthering this search, what does come up is the same photo of Charles Palmer's #34 corner store, but with the entire entranceway shown, and the full banner above it. Indeed it is as has all been figured out and described, including NU PAK. Way up high is the lower portion of CHAS, as anticipated, above the upper triangle, before the photo ends. To view as much of this photo as there appears to be available, visit this website and look for product code: E-0094.

|

Portion of an image shared on Pinterest by Alan Russell. View full image at his link.

|

This Victorian era style of building is commonly described as "terraced". If strictly residential, similar construction in North America would be known as townhouses. In London, in areas zoned as mixed use, a storefront at ground level with one or two "flats" (apartments) above would be commonplace. The flats would either be accessed from the rear or from an extra door and staircase from the front. The residents of the flats may or may not be involved in the operation of the business below. While this type of mixed use architecture is very common in North America, theer is no specific term that describes it. Apartments above storefronts is about all one can say.

As can be seen in this photo, the block is comprised of slightly varying archtecture. This may have happened over time with renovations being done by the different owners. It was not uncommon, though, for a block to have been originally contructed by different builders, or at different times, perhaps in sub-blocks of two to four units. This may account for variances of brick colour or composition, window appearance, store front design or rooftop inconsistencies. The end result would still be a monoblock. Similar terraced construction was used for the strictly residential areas off the main streets.

The building on the NE corner of Chatsworth and Dunlace numbered 36 has a visible "datestone" in its front that reads 1870. This can be seen if Google Streetview is oriented to show it. That would date the block containing the lower-numbered 34 to be the same, or slightly prior, in year of construction.

Now, about the irregularity in William Squires' stated work location...

In the 1901 Directory (image 115 of 928) and the 1904 Directory (page 85, image 94), 84 Chatsworth is occupied by William Bowers, greengrocer. Presumably he was there in the intervening years also.

This is not in agreement with the statement made in the Barnardo's documents that contained this record of the family, written in 1903 by a caseworker.

"For more than eleven years the father was carman, at a wage of 25/- per week, to Messrs. Palmer & Co., grocers, 84, Chatsworth Road, Hackney, and from the head of the firm our agent learnt that he bore an exemplary character, and was very much liked by everyone."

The caseworker got their information from the "head of the firm". But Kelly's Directories have also been reliable.

How can two contradictory facts be true? Two theories: the first is that Messrs. Palmer & Co. included locations that did not only go under the name Palmer. Certainly plausible. The 'head of the firm" is an apt description of owner, and it also makes it sound like this is a company with more than one outlet, that could possibly have had subsidiaries. William Bowers was operating as a greengrocer, in the same line of business. Could William Squires have been working for Palmer's company, but primarily out of 84 Chatsworth as a subsidiary?

The second theory involves 84 being a typo. The original Barnardo's document is typewritten, presumably from hand-written notes made in the field or during admission, or from a previous document made during the acquaintance stage, like in the letter from the Charity Organisation Society identifying the family was in need. Charles Palmer was in the Directory as having a store at 34 Chatsworth, and one at 116 Chatsworth. What if the 84 should have been 34? This is a much simpler theory, but it is still factually plain in the typewritten report that the address was 84. Does this hold up as fact?

A further challenge to the address being 84... 34 is a corner location, the SE corner of Chatsworth and Dunlace Road. 84 Chatsworth is a very typical, and small, location in the middle of the block. If Charles Palmer owned numerous locations, it might be that he could afford better locations. And 116 appears to have been a corner lot also, at Lockhurst Street. Today, 112 is the second address SE from Lockhurst, 116 would have been on the opposite (NE) corner. (See more about the demise of 116 Chatsworth several paragraphs down). Palmer would have had two preferred corner locations, about a 4-minute walk apart, serving two different neighbourhoods, over the bland mid-block store at 84. 133 High Street in Walthamstow is a mid-block location, but it is of decent size. 123 Stoke Newington Road, is of typical storefront size. Very difficult to tell what 64 High Street in Homerton may have looked like using Streetview since the area has greatly changed. In any case, it would be unlikely that one owner would have three stores on Chatsworth, within four minutes of each other, no more than forty doors apart.

|

|

|

34 Chatsworth, on the SE corner of Dunlace, has been occupied since at least 2014 by a Turkish restaurant, with Turkish cuisine, named Pivaz. Prior to that, and perhaps since Charles Palmer occupied the site, 34 Chatsworth had been a grocery store. A corner location with an array of awnings allows goods to be displayed outside (weather permitting), effectively enlarging the merchandise area. Perhaps especially so for a grocery store.

So, was William Squires employed at 84 Chatsworth, working at a subsidiary of Charles Palmer's, or at 34 Chatsworth, an address known to be operating under the name of Charles Palmer? Awaiting further evidence, but leaning strongly towards his address of employment having been #34.

In the 1906 directory, 84 Chatsworth was occupied by Henry Cooling, Furniture Dealer. It is believed that 1906 was also the first year that Arthur Toms eel pie house started at this address. In the 1907, 1908, 1911, 1916 and 1919 directories, 84 Chatsworth is occupied by Arthur Toms. See the story about the Arthur Toms sign revealed in a modern renovation of 84 Chatsworth several paragraphs above.

In the 1904, 1906, 1907, 1908, 1911, 1916 and 1919 directories, 34 and 116 Chatsworth are under the name Walter Allen, grocer. No need to verifiy every year there, enough to know that Charles Palmer was no longer operating a business at these addresses. Did all of Palmer's locations transfer to Walter Allen? In 1904, 1905 (alphabetical by name), 1907 and 1908, 47 & 64 High Street Homerton still show Charles Palmer, grocer. In 1904, 133 High Street Stoke Newington does not. So, something happened, and Palmer did give up some of his locations, but it is all irrelevant now to the story of William Squires following his death in 1903, yet somewhat interesting all the same.

Note: the gaps don't mean absence, but rather continuity across. And first and last years shown do not necessarily mean that these were the first and last years of occupancy, just that these were the first and last entries I was able to find or did look for.

Note for future research: If possible, locate a newspaper ad for Charles Palmer's grocery stores for the year 1903. Use it for colour and look for the currency of the addresses it may list in company description, store hours, etc. Sometimes the directories are a year out.

The residential address of Mary Ann Squires and children on October of 1903 -- 13 Maclaren Street, Hackney, London, UK.

The family address at the time of the social services proceedings in October of 1903 was 13 Maclaren Street, Hackney (or, more specifically, Clapton Park ward, South Hackney). It is my belief at present that the family moved here from Blurton Road after the father died to get some rent relief.

There is a very high probability that this address was the birthplace of Amy. Godmanchester, the birthplace of William and where his parents were in 1903 is about 65 miles north of Hackney, the northernmost borough of London before the creation of Greater London in 1963. Mary Ann's birthplace was about 7 miles away in Paddington W. Kensington. Alice would have been born when the family was at 120 Blurton Road.

Another significance of 13 Maclaren Street is that this is the last place Alice and Amy lived with their mother. It is worth some space here to talk about where Maclaren was and what happened to it, even if for others who may find this page when wondering.

Maclaren Street cannot be found on a modern map. In order to find out where it was, I tried looking on old maps, but London is a big place and I wasn't having any luck. So I tried a different approach and searched instead for a mention of Maclaren in relationship to a street that does exist today. I found this text somewhere... "the part of Clapton Park Ward to the south of a line drawn along the centres of Glenarm Road, Glyn Road and Redwald Road to its junction with Maclaren Street". This was enough for me to find Redwald and see where a junction with Maclaren might be. I looked on an old map from 1899 and found it. Sadly, the map is a study in poverty, and the colouring of the street indicates that the residents were not doing very well.

|

|

|

| - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- 1 ----- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2 |

|

- Legend

|

This is a snip of one map in a series of twelve maps originally used to illustrate the levels of poverty in London, in 1899. The twelve maps, assembled together, cover all of London. The map series was a companion to Charles Booth's Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London from which I have drawn information on the occupation of carman (click Back to return here if you follow the link). (The other titles in the series, for the most part, can be found and read here.) The series used Ordnance Survey maps as their foundation. A great many terrific maps can be found at the National Library of Scotland, like this one that will show Blurton Road when drilled down into.

The Charles Booth Online Archive site has an interactive version of the map at the National Library of Scotland with overlays and a search function, as well as an extended explanation of the colour coding. Chatsworth Road (in Lower Clapton), which runs roughly north-south, is indicated above at E1. 120 Blurton Road (where the familiy lived) would be east of Chatsworth, almost to Glyn, about where the "R" in Blurton Rd. is, south side. Maclaren Street (where the family lived when social services stepped in) is indicated at E2.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

taken by TF

|

222

|

223

|

224

|

225

|

226

|

227

|

228

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

229

|

230

|

231

|

232

|

233

|

234

|

235

|

236

|

The notebooks that were used by the data gatherers for Booth's books have been digitized and are available online. I believe the notes were handwritten by data gatherers working for Booth with comments from Inspector Thomas Fitzgerald of Bethnal Green police station. The latter half of this notebook is hard to read, but there is enough of interest in it to make it worth trying. The notes on pages 222 to 236 make mention of the Chatsworth neighbourhood, including Maclaren. View the pages at the source, or view the pertinent pages here. A foreboding remark in the notes, on page 231, describes Maclaren Street as being perhaps a little better than it was painted in the study, but expected to later decline: "Pedro Street, a distinct purple, 'All Saints', a red brick church, is in this road, and there is some open, unbuilt space opposite (the church). The houses have small gardens behind, but the impression left is that Pedro Street is on the road to squalidity. McLaren Street which is a turning south out of Rushmore Road, is the same as then Pedro Street, tho' the map marks it light blue." Some 50 years later, Maclaren is no more.

There are two ways to get to where Maclaren Street was from 120 Blurton Road. One is to go north on Glyn then east on Rushmore, then east to beyond Pedro Street, but not as far as Oswald Street. As you get east of Glyn Road, the reconstruction efforts in the area have wiped out any chance of seeing the Maclaren Street of 1903.

The corner of Rushmore Road and Maclaren Street would have been about where the three blue pillars are blocking cars from entering the pedestrian square of this "shopping precinct" (left end of the wider of these two images), a combination of stores and residences.

|

|

|

|

Click to enlarge and view the cleaned up areas at 116 Chatsworth, 120 Blurton (blue x), and numbers 20 through 28 on Maclaren.

|

Click to enlarge and view the changes in the area around Maclaren that took place post-war. (The overlay was snipped from image 3.)

|

Click to enlarge and view the changes in the area post-war. Maclaren and 116 Chatsworth no longer exist. 120 Blurton is now in a complex.

|

To help confirm the timeline for the demise of Maclaren Street... this portion of an aerial view (© historicengland.org.uk) of the neighbourhood taken in 1945 (post-war) shows Maclaren. It has a slight kink in it that kept it from going straight on into Oswald Street. Today, Oswald no longer intersects with Rushmore where Maclaren ended, it takes a turn towards Pedro and intersects there instead, like a crescent. The middle image shows a modern overlay of the reconstruction on top of the 1945 map, the right image (© Google 2024, Google Earth) shows the location after reconstruction today.

I did not realize until 5/23/2025 that this picture series is doubly important in what it shows. Yes, it shows that the neighbourhood around Maclaren was rebuilt sometime after 1945, but there has been no explanation as to why as yet, especially considering that similar houses in the vicinity have survived to this day. It occurred to me that perhaps the area had been destroyed - in a fire perhaps or, of course, the bombing of London in WWII. I was able to find a map that showed Maclaren had suffered damage centering on the houses even-numbered 20 through 28 on the west side. Judging by the resulting damage, the bomb strike was centered on the rear of the house, or the yard, of #24. Lesser damage occurred to the area around this center. Enough damage, it seems, to have resulted in the tearing down of the entire street and houses around it as opposed to rebuilding them.

120 Blurton on the 1945 maps show the same kind of demolition and clearing that followed bomb strikes. The leftmost image has a blue X where 120 Blurton is, visible when enlarged. (There is a blue arrow pointing at it in the upcoming Bomb Damage Map.

And I also didn't realize that the area that looks a little bit like cloud cover is actually flattened land, too. That's the corner where 116 Chatsworth (Charles Palmer's second store on Chatsworth) had once stood. The area was hit by a German V1 bomb making that half a block and some properties around it "damaged beyond repair".

The streets around Chatsworth Road and Lockhurst Street had been lined with modest terraced homes built for working families. In the postwar years, this destruction prompted clearance and redevelopment. Six modern (for the time) identical three-storey apartment buildings, each containing perhaps 12 units if balconies are counted, were constructed as part of the government's overall urban renewal efforts. The six buildings form a circle, one side of each close to the road it is on. Some "gated" parking and a bit of green space is available at its core. The past remains in that the half of the block that wasn't destroyed is today largely as it was since it was originally constructed. Chatsworth Estate, used to describe the reconstructed half-block, is a misnomer, it is not an "estate" at all. The surrounding area affected by the blast has been restored, or re-built, to its own end.

View the complex as it was from the air in 2025 on Google maps.

V1: Vergeltungswaffe 1. Vengeance weapon 1. Flying bomb. "Buzz bomb". "Doodlebug". Predecessor to the V2. See and hear.

London County Council Bomb Damage Map

This is a link to londonpicturearchive.org.uk, to the highly-detailed London County Council (LCC) Bomb Damage Map. It is a bit difficult for someone unfamiliar with the layout of London to find Lower Clapton on it, so one trick I used was setting a destination of 34 Chatsworth in Google maps then putting a street name from the LPA map in as a starting point. The path on the Google map would indicate which direction to move in on the LPA map. Once over the area, zoom in to view the neighbourhood in great detail.

What is shown here (in a "large" circle) is where a V1 flying bomb hit a neighbourhood of interest. 116 Lockhurst, at the NE corner of Chatsworth and Lockhurst, is the second store Charles Palmer operated on Chatsworth, along with #34 back in 1903. This is the reason why a period building cannot be found at this address today. The area was rebuilt post-war.

What is also shown here (blue arrow) is the address of 120 Blurton Road, where the Squires family lived up until the spring of 1903, when William Squires was alive. (The family moved to 13 Maclaren Street soon after his death.) The dark purple colour indicates irrepairable damage caused by a smaller bomb strike with a ring of what is probably orange around the center indicating blast damage (not structural). This explains why Streetview does not show period architecture at that location today, this would have been rebuilt post-war. Aside from the V1 hit, Chatsworth seems to have been otherwise unscathed.

Note: to view the full and proper map, follow the link above. This is a snip from a map image at Flickr.

|

Key:

BLACK – Total destruction.

PURPLE – Damaged beyond repair.

DARK RED – Seriously damaged; doubtful if repairable.

LIGHT RED – Seriously damaged; but repairable at cost.

ORANGE – General blast damage; not structural.

YELLOW – Blast damage; minor in nature.

LIGHT GREEN or LIGHT BLUE – Clearance areas.

SMALL CIRCLE – V-2 Rocket.

LARGE CIRCLE – V-1 Flying Bomb.

|

|

Note to insert better picture of 116 Chatsworth from the bomb damage map when permitted to do so.

|

|

This next image is from theundergroundmap.com , a site with a brief history of Chatsworth Road as well as hundreds of other streets and roads. The site has maps dating back to 1800, done as overlays, with this one dated 1950, five years after WWII. Where damage had been done to a location, the buildings there are missing. This dates the post-war re-construction to have been done during the 1950's and perhaps into the early 1960's.

The numbering scheme on Maclaren is shown as west-even, east-odd, north-high, south-low. Redwald and Maclaren meet but do not intersect. The numbering of Redwald continues one house in the direction of Maclaren and Maclaren begins one house onto Redwald. Number 13 Maclaren, where the Squires family lived during 1903, is indicated in yellow. The bomb strike location on Maclaren is shown as empty lots on the "even" side of the street. Some area around did suffer blast damage, though "minor in nature".

Another observation from this map is the way that Redwald Road conjoined Maclaren Street. If one considers the houses on this map on the east side of Maclaren, the odd-numbered side, only for the reason that Redwald is continued around the corner by one house, numbered 79, with the next house numbered 1 Maclaren, does #13 land where it does.

If you use Google Street View to "walk" south instead on Glyn, many old house fronts can be seen on the west side. When turning onto Redwald Road, you will be entering into an area known as Clapton Park, Nye Bevan and Millsfield Estates. This is one of the few places where the images allow you to see the grade - you will be looking downhill. At the point on Redwald where it once conjoined Maclaren Street, Redwald instead now continues on through to Daubeney Road. (No explaining how cars can be parked facing different directions on the same side of some streets, by the way.)

Looking north today (from Redwald) as if looking north on Maclaren, one can see instead this building complex. A sign just off the image to the right identifies this as Clapton Park Estate. At the far end, the south side of the "shopping precinct" can be seen. The image on the right is looking south from the "shopping precinct", from the northern end of Maclaren.

|

|

When built, houses on Maclaren Street probably started out looking as good as this series of two-storey houses on nearby Roding Road (left), but more than likely had the architecture of this series of less ornate three-storey houses on Glyn. No telling how many families lived in each house, or if they were rented or owned, though this information may be on census reports of the time. In the case of the Squires family, the Barnardos documentation noted that, when living at 13 Maclaren, the family had just two small rooms, renting for 5/- per week, and was three weeks in arrears. The family almost assuredly had more space when the father was alive and they were living on Blurton Road. If the houses on Maclaren at that time were being used for low income residents as the map above indicates, the houses may also have suffered from lack of care and maintenance, leading to their demolition in favour of the shopping precinct that replaced them.

Of note: the count of rooftops on a modern satellite view does not exactly jibe with the count of house-like rectangles on the map from 1899 (above) for most of the surrounding streets, so the rectangles on the map may only be representative of housing in general terms, perhaps making my determination of the location of 13 Maclaren less than accurate.

Education and schooling in 1903 London...

William's and Mary Ann's children numbered five at the beginning of 1903, and increased to six after the death of William. The ages of the children were: 8 (male), then 7, 4, 3, and 2 (female) with Amy born in August.

Schooling had been instituted for all children aged 5 to 10 in London since 1870. This would put William and Harriet in school while Florence, Ethel and Alice were not of age. Pre-school would have been for the well-to-do families, not for this Squires family. This would mean Mary Ann would have had to attend to the three youngest during the day, then have perhaps a small amount of help from the two oldest when they came home. To be able to work, Mary Ann would have had to rely on neighbours and friends, and any relatives that could come to pick up a child or two or who could stay awhile and sit. While husband William was alive, Mary Ann may have been able to work during William's off hours. As it does today, the illness of a child completely disrupts any plans a family may have.

The school the children likely attended was Rushmore Road School (opened in 1877, renamed Rushmore Primary School in 1951, photo taken 1908 at layersoflondon.org).

This school was about a four-block walk from 120 Blurton where the family lived: 330 child-steps in approximation to Chatsworth, another 300 child-steps to Elderfield Road, 160 child-steps to Rushmore Road then another 190 child-steps along Elderfield to the front door of the school - well over a thousand if you add for puddles, dog-petting, chatting with neighbours; store windows and street-crossings; walking backwards, running, hops, skips and jumps; avoiding enemies and meeting up with friends along the way. And a bit longer than that if there's a ha'penny in the pocket.

Students would have been taught "the three R's", reading, (w)riting and (a)rithmetic, with perhaps some religious instruction focused on the Bible: this, with an emphasis on rote learning and discipline. It wouldn't be until later grades that history, geography and the sciences would be taught, subjects requiring critical thinking. Physical activity would have included sports, track and field events, and gymnastics, as well as basic breathing exercises and posture correction. "Open-air" schools were more than trendy in urban settings, with as much fresh air let in as a school could let.

A school's educational direction was to teach self-reliance through independent work. Given the neighbourhood, higher learning, beyond perhaps the age 13 or 14, would be out of the question. Students were being prepared for entry into the workforce rather than for further education. And in the Squires family situation, while it may have been possible that the children would have all gotten through public school, this was not the case following the father's death.

In retrospect, William's education did eventually lead to that decent job at the post office, while the girls' education led to more domestic roles - typical of the time. As noted elsewhere on this page, the 1911 census provides a snapshot: 15-year-old William was employed as a warehouseman's assistant, 14-year-old Harriet was employed as an apprentice blouse maker, Florence and Ethel, ages 13 and 11, were in school, and Alice and Amy, ages 10 and 8, were in their last year living at Beckley School cottage, attending Beckley School, before they would emigrate in 1912. Sadly, their education in rural Ontario would become sporadic and abbreviated. (Note: this link returns a reader to an earlier point on this page. Use the Back button, if you choose to follow the link, to return here.)

Goad's old street maps, fire insurance maps...

...have a great amout of detail in them. They are very representative of neighbourhoods and their occupants. These maps, dating back to the 1800's, can be hard to find, but are worth looking for. Well worth the time spent locating them.

A reminder... Alice's story picks up again on the page for Archibald Thomas Longhurst, the Canadian whom Alice (Lulu) married.

How this family connects...

The generations to present include :

Charles SQUIRES / Mary Ann LEA

William SQUIRES (Sr.) / Harriett HOWELL

William SQUIRES (Jr.) / Mary Ann HARROWELL

Archibald Thomas LONGHURST / Alice Violet "Lulu" SQUIRES

Alfred Thomas Burton LONGHURST / Theresa Mary BURKE

Image credits...

Street View imagery is © Google.

Census page imagery is © ________ .

Other images © as noted with each instance.

Used under fair dealing/fair use for historical and educational reference.